Goodfellow Deep Learning — Chapter 7.8: Early Stopping

Overview

Early stopping is a simple yet effective regularization technique that stops training when validation performance begins to degrade.

1. The Overfitting Problem

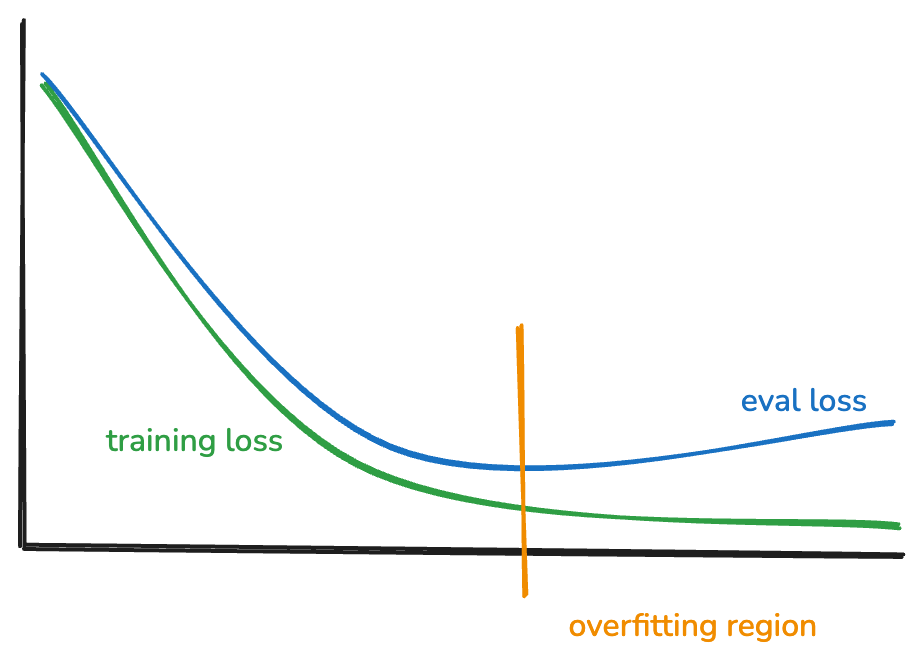

Observation: Overfitting almost always occurs during training.

What happens:

- Training error continues to decrease

- Validation error initially decreases, then starts increasing

- The gap between training and validation error grows

- Model memorizes training data instead of learning generalizable patterns

Solution: Stop training when validation error reaches its minimum.

2. Two Approaches to Early Stopping

Split data into training \((x, y)\) and validation \((x_{\text{valid}}, y_{\text{valid}})\):

Approach 1: Find Optimal Steps, Then Retrain

- Train on \((x, y)\) while monitoring \(y_{\text{valid}}\)

- Identify the optimal number of steps \(\tau^*\) where validation error is minimized

- Retrain from scratch on full dataset for exactly \(\tau^*\) steps

Advantage: Uses all data for final training

Disadvantage: Requires two full training runs

Approach 2: Keep Best Model

- Train on \((x, y)\) while monitoring \(y_{\text{valid}}\)

- Keep a copy of the model whenever validation performance improves

- Stop when validation error stops improving

- Use the saved best model

Advantage: Only requires one training run

Disadvantage: Validation data is not used for training

3. Costs of Early Stopping

Data requirements:

- Need to hold out a portion of data as validation set

- Reduces effective training data size

- Validation set typically 10-20% of total data

Computational requirements:

- Need to keep a copy of the best-performing model

- Requires periodic evaluation on validation set

- May need multiple checkpoints if using approach 1

4. Benefits of Early Stopping

Regularization:

- Prevents overfitting without modifying the loss function

- Acts as implicit L2 regularization (proven mathematically below)

- No hyperparameter tuning needed for regularization strength

Efficiency:

- Saves computation by stopping early

- Automatic hyperparameter selection (number of iterations)

- Often faster than training with explicit regularization to convergence

Simplicity:

- Easy to implement

- Widely applicable across different model types

- Works well in practice without fine-tuning

5. Mathematical Connection to L2 Regularization

Gradient Descent Update Rule

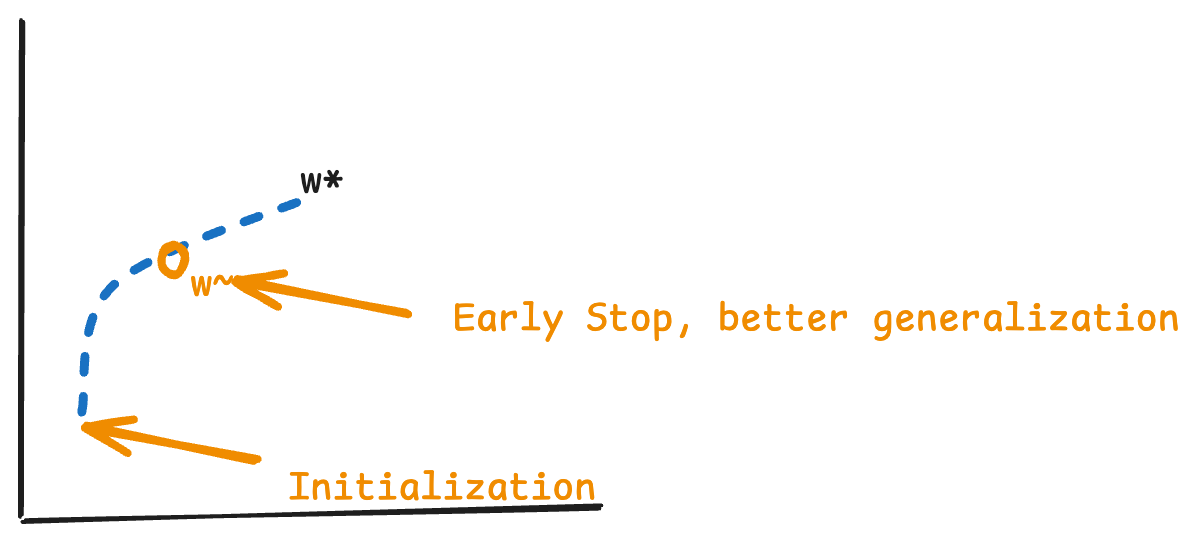

Starting from a quadratic approximation around the optimal weights \(w^*\):

Equation 7.33 - Quadratic approximation of loss:

\[ \hat{J}(\theta) = J(w^*) + \frac{1}{2}(w - w^*)^T H(w - w^*) \]

where \(H\) is the Hessian matrix at \(w^*\).

Equation 7.34 - Gradient:

\[ \nabla_w \hat{J}(w) = H(w - w^*) \]

Equation 7.35 - Gradient descent update:

\[ w^{(\tau)} = w^{(\tau-1)} - \epsilon \nabla_w \hat{J}(w^{(\tau-1)}) \]

Equation 7.36 - Substituting the gradient:

\[ w^{(\tau)} = w^{(\tau-1)} - \epsilon H(w^{(\tau-1)} - w^*) \]

Equation 7.37 - Rearranging:

\[ w^{(\tau)} - w^* = (I - \epsilon H)(w^{(\tau-1)} - w^*) \]

Eigendecomposition of Hessian

Equation 7.38 - Decompose \(H = Q\Lambda Q^T\):

\[ w^{(\tau)} - w^* = (I - \epsilon Q\Lambda Q^T)(w^{(\tau-1)} - w^*) \]

Equation 7.39 - Multiply both sides by \(Q^T\):

\[ Q^T(w^{(\tau)} - w^*) = (I - \epsilon \Lambda)Q^T(w^{(\tau-1)} - w^*) \]

Deriving the Recursive Formula

Since \((I - \epsilon\Lambda)\) is a constant diagonal matrix, we can apply this recursion:

Step 1 - After 1 iteration:

\[ Q^T(w^{(1)} - w^*) = (I - \epsilon \Lambda)Q^T(w^{(0)} - w^*) \]

Step 2 - After 2 iterations:

\[ \begin{aligned} Q^T(w^{(2)} - w^*) &= (I - \epsilon \Lambda)Q^T(w^{(1)} - w^*) \\ &= (I - \epsilon \Lambda)Q^T(I - \epsilon \Lambda)(w^{(0)} - w^*) \\ &= (I - \epsilon \Lambda)^2 Q^T(w^{(0)} - w^*) \end{aligned} \]

Step 3 - After 3 iterations:

\[ \begin{aligned} Q^T(w^{(3)} - w^*) &= (I - \epsilon \Lambda)Q^T(w^{(2)} - w^*) \\ &= (I - \epsilon \Lambda)Q^T(I - \epsilon \Lambda)^2(w^{(0)} - w^*) \\ &= (I - \epsilon \Lambda)^3 Q^T(w^{(0)} - w^*) \end{aligned} \]

General pattern - After \(\tau\) iterations:

\[ Q^T(w^{(\tau)} - w^*) = (I - \epsilon \Lambda)^\tau Q^T(w^{(0)} - w^*) \]

Assuming Zero Initialization

Equation 7.40 - If \(w^{(0)} = 0\):

\[ \begin{aligned} Q^T(w^{(\tau)} - w^*) &= (I - \epsilon \Lambda)^\tau Q^T(0 - w^*) \\ &= -(I - \epsilon \Lambda)^\tau Q^T w^* \end{aligned} \]

Therefore:

\[ Q^T w^{(\tau)} = Q^T w^* - (I - \epsilon \Lambda)^\tau Q^T w^* \]

\[ Q^T w^{(\tau)} = [I - (I - \epsilon \Lambda)^\tau] Q^T w^* \]

L2 Regularization Solution

Equation 7.41 - L2 regularized solution:

\[ Q^T \tilde{w} = (\Lambda + \alpha I)^{-1} \Lambda Q^T w^* \]

Equation 7.42 - Rewriting:

\[ Q^T \tilde{w} = [I - (\Lambda + \alpha I)^{-1} \alpha] Q^T w^* \]

Equivalence Condition

Equation 7.43 - Comparing equations 7.40 and 7.42:

If we can set:

\[ (I - \epsilon \Lambda)^\tau = (\Lambda + \alpha I)^{-1} \alpha \]

then early stopping is equivalent to L2 regularization.

6. Relationship Between Training Steps and Regularization Strength

Deriving \(\tau\) from \(\alpha\)

Mathematical tools:

- Logarithm properties: \(\log(ab) = \log(a) + \log(b)\) and \(\log(a^b) = b\log(a)\)

- Taylor series approximation: \(\log(1 + x) \approx x\) and \(\log(1 - x) \approx -x\)

Starting from equation 7.43:

\[ \tau \log(I - \epsilon \Lambda) = \log((\Lambda + \alpha I)^{-1} \alpha) \]

Right side:

\[ \log((\Lambda + \alpha I)^{-1} \alpha) = -\log(\Lambda + \alpha I) + \log(\alpha) \]

Factor out \(\alpha\):

\[ \Lambda + \alpha I = \alpha\left(\frac{\Lambda}{\alpha} + I\right) \]

Therefore:

\[ -\log(\Lambda + \alpha I) + \log(\alpha) = -\log(\alpha) - \log\left(\frac{\Lambda}{\alpha} + I\right) + \log(\alpha) = -\log\left(\frac{\Lambda}{\alpha} + I\right) \]

Left side using Taylor approximation:

\[ \log(I - \epsilon \Lambda) \approx -\epsilon \Lambda \]

Right side using Taylor approximation:

\[ \log\left(I + \frac{\Lambda}{\alpha}\right) \approx \frac{\Lambda}{\alpha} \]

Combining:

\[ \tau(-\epsilon \Lambda) \approx -\frac{\Lambda}{\alpha} \]

Equation 7.44 - Solving for \(\tau\):

\[ \tau \approx \frac{1}{\epsilon \alpha} \]

Equation 7.45 - Solving for \(\alpha\):

\[ \alpha \approx \frac{1}{\epsilon \tau} \]

Key Insight

The number of training steps \(\tau\) is inversely proportional to the L2 regularization strength \(\alpha\).

Interpretation:

- More training steps (\(\tau\) large) ↔︎ Weaker regularization (\(\alpha\) small)

- Fewer training steps (\(\tau\) small) ↔︎ Stronger regularization (\(\alpha\) large)

- Early stopping implicitly applies L2 regularization with strength \(\alpha \approx \frac{1}{\epsilon \tau}\)

Practical implication: Choosing when to stop training is equivalent to choosing the regularization strength.

Key concepts:

- Early stopping: Stop training when validation error stops improving

- Two approaches: Find optimal steps and retrain, or keep best model

- Costs: Requires validation data and model checkpointing

- Benefits: Simple, effective, computationally efficient regularization

- Mathematical equivalence: Early stopping ≈ implicit L2 regularization

- Inverse relationship: \(\tau \approx \frac{1}{\epsilon \alpha}\) (more steps = less regularization)

Source: Deep Learning Book, Chapter 7.8