Goodfellow Deep Learning — Chapter 9.4: Convolution and Pooling as an Infinitely Strong Prior

Overview

This section examines how convolutional architectures encode strong assumptions about the data:

- Structural priors: Local connectivity and weight sharing as architectural constraints

- Infinitely strong prior: CNNs as restricted fully connected networks

- Translation invariance: How pooling enforces spatial insensitivity

- Task-dependent effectiveness: When these priors help or hurt performance

- Domain specificity: Why convolution is not universally appropriate

Understanding CNNs as embodying strong priors helps explain both their effectiveness on images and their limitations on other data types.

1. Convolution and Pooling Introduce Strong Structural Priors

Fully connected networks have an enormous amount of freedom and require vast amounts of data.

Convolution imposes two major constraints:

- Local connectivity: Each hidden unit only interacts with a small spatial neighborhood

- Weight sharing: The same filter is applied everywhere

These constraints act as strong priors that greatly reduce model complexity, improve statistical efficiency, and guide learning toward functions that are meaningful for images.

Why this matters: Without these priors, a network would need to learn separately that edge detection at position (10, 10) should use the same weights as edge detection at position (50, 50). The convolutional prior encodes this knowledge directly into the architecture.

2. A Convolutional Network as a Fully Connected Network with Infinitely Strong Restrictions

If we start with a fully connected model and then force: - All weights outside a local window to be exactly zero - All local windows to reuse the same set of weights

We obtain a convolutional network.

This can be interpreted as introducing an “infinitely strong prior” — only a very specific family of functions (local, translation-equivariant ones) is allowed, and all others are ruled out by architectural design.

Comparison:

| Aspect | Fully Connected | Convolutional |

|---|---|---|

| Weight constraints | None (all weights independent) | Local + shared weights |

| Prior strength | Weak (relies on data) | Infinitely strong (architectural) |

| Parameter efficiency | Low (millions of parameters) | High (thousands of parameters) |

| Inductive bias | Minimal | Strong (locality + stationarity) |

Interpretation: A Bayesian prior assigns probability to different functions. An “infinitely strong prior” assigns probability 1 to functions satisfying the architectural constraints and probability 0 to all others.

3. Pooling Adds Another Infinitely Strong Prior: Translation Invariance

Pooling enforces the assumption that the exact spatial location within a small region does not matter.

Only the presence of a feature in the region matters.

For each pooling window: - The output is determined solely by the largest (or average) activation - Not by where inside the region the activation occurs

This encodes a strong prior that the model should be insensitive to small translations, reducing variance and improving robustness.

Example: Consider detecting the edge of an object. With pooling: - Edge at pixel (15, 20): max pool value ≈ 0.9 - Edge at pixel (16, 21): max pool value ≈ 0.9 (nearly unchanged)

The classifier sees nearly identical features regardless of the 1-pixel shift.

4. These Priors Can Help or Hurt, Depending on the Task

When the Priors Help

For image classification, these priors are extremely useful because natural images: - Contain localized structures (edges, textures, objects) - Exhibit stationarity across spatial positions (statistics don’t change with location) - Benefit from translation invariance (a cat is a cat regardless of position)

The strong priors dramatically reduce the amount of data needed to train effective models.

When the Priors Hurt

For tasks requiring precise spatial relationships — e.g., localization, medical imaging, fine-grained keypoint prediction — pooling may discard important information and increase bias.

Example problems: - Object localization: Need exact coordinates, but pooling discards spatial precision - Medical imaging: Exact tumor position matters, not just presence - Pose estimation: Keypoint coordinates must be precise

Some CNN variants (e.g., Inception, Szegedy et al.) redesign pooling strategy to avoid this issue.

Trade-off: Strong priors reduce variance (need less data) but increase bias (restrict function class). The optimal choice depends on whether the task aligns with the prior assumptions.

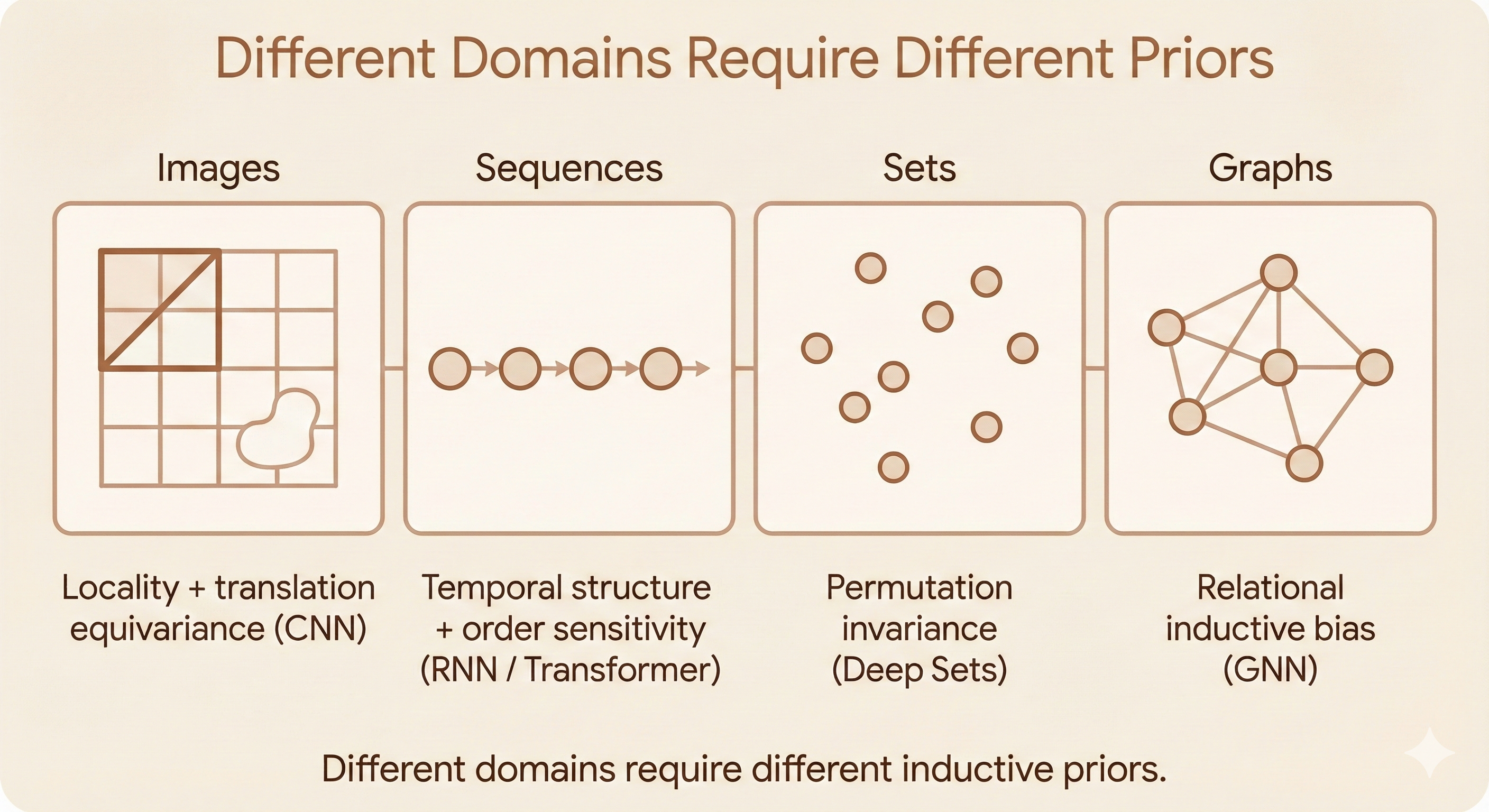

5. Different Domains Require Different Priors; Convolution Is Not Universally Appropriate

The section emphasizes that convolution + pooling is very effective for images, but the same assumptions may not hold for:

- Sets (requiring permutation invariance)

- Graphs (requiring relational/structural priors)

- Point clouds or 3D geometric data

- Tasks where invariance must be learned, not assumed

Key insight: The success of CNNs on images comes from the alignment between: 1. The architectural prior (locality + translation equivariance) 2. The statistical structure of natural images

For other data types, different architectures with different priors may be more appropriate: - Graph neural networks: For relational data with graph structure - Transformers: For sequence data with long-range dependencies - Set networks: For permutation-invariant tasks - Equivariant networks: For data with specific symmetries (rotation, scale, etc.)

Figure: Different domains require different architectural priors - convolution excels for images due to locality and translation equivariance, while other data types benefit from architectures with priors matching their structure (graphs, sequences, sets, etc.).

Figure: Different domains require different architectural priors - convolution excels for images due to locality and translation equivariance, while other data types benefit from architectures with priors matching their structure (graphs, sequences, sets, etc.).

Summary

| Concept | Key Idea |

|---|---|

| Architectural Prior | Convolution and pooling encode assumptions directly into network structure |

| Infinitely Strong Prior | CNN = fully connected network with zero probability on non-local, non-shared weight configurations |

| Structural Constraints | Local connectivity + weight sharing reduce parameters and improve sample efficiency |

| Translation Invariance | Pooling enforces insensitivity to exact spatial locations within neighborhoods |

| Bias-Variance Trade-off | Strong priors reduce variance but increase bias if assumptions don’t match task |

| Domain Specificity | Convolution is optimized for images; other domains need different architectural priors |

Fundamental principle: The effectiveness of an architecture depends on how well its built-in priors match the statistical structure of the data and task requirements. CNNs succeed on images because their priors (locality, stationarity, translation invariance) align perfectly with the properties of natural images.