Lecture 31: Change of Basis and Image Compression

Overview

This lecture explores how change of basis enables image compression:

- Image representation as high-dimensional vectors

- JPEG compression using Fourier basis

- Wavelet basis as an alternative

- Properties of good bases for compression

- Change of basis formulas and similar matrices

1. Lossy Compression

A gray \(512 \times 512\) image contains 262,144 pixels.

We use \(x_i\) to represent a pixel, \(0 \leq x_i \leq 255\) (8 bits, \(2^8 = 256\)).

The entire image can be represented as a vector:

\[ x \in \mathbb{R}^n, \quad n = 512^2 = 262,144 \]

Figure: Image representation as a vector - each pixel becomes a component, transforming the 2D image into a point in high-dimensional space.

Figure: Image representation as a vector - each pixel becomes a component, transforming the 2D image into a point in high-dimensional space.

Challenge: Storing 262,144 numbers requires significant memory. Can we represent the same image with fewer numbers by choosing a better basis?

2. JPEG Compression

JPEG (Joint Photographic Experts Group) is fundamentally about changing the basis.

Standard Basis

The standard basis in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) consists of unit vectors:

\[ \begin{bmatrix}1\\0\\0\\\vdots\end{bmatrix}, \quad \begin{bmatrix}0\\1\\0\\\vdots\end{bmatrix}, \quad \ldots, \quad \begin{bmatrix}0\\0\\\vdots\\1\end{bmatrix} \]

Each basis vector represents a single pixel.

Better Basis

A better basis might have vectors that capture image structure:

\[ \begin{bmatrix}1\\1\\1\\1\\\vdots\\1\end{bmatrix}, \quad \begin{bmatrix}1\\1\\-1\\-1\\\vdots\\-1\end{bmatrix}, \quad \begin{bmatrix}1\\-1\\1\\-1\\\vdots\\-1\end{bmatrix}, \quad \ldots \]

These vectors capture patterns like: - Constant intensities (first vector) - Low-frequency variations (second vector) - Higher-frequency patterns (remaining vectors)

Fourier Basis

JPEG uses the Fourier basis for compression:

Steps:

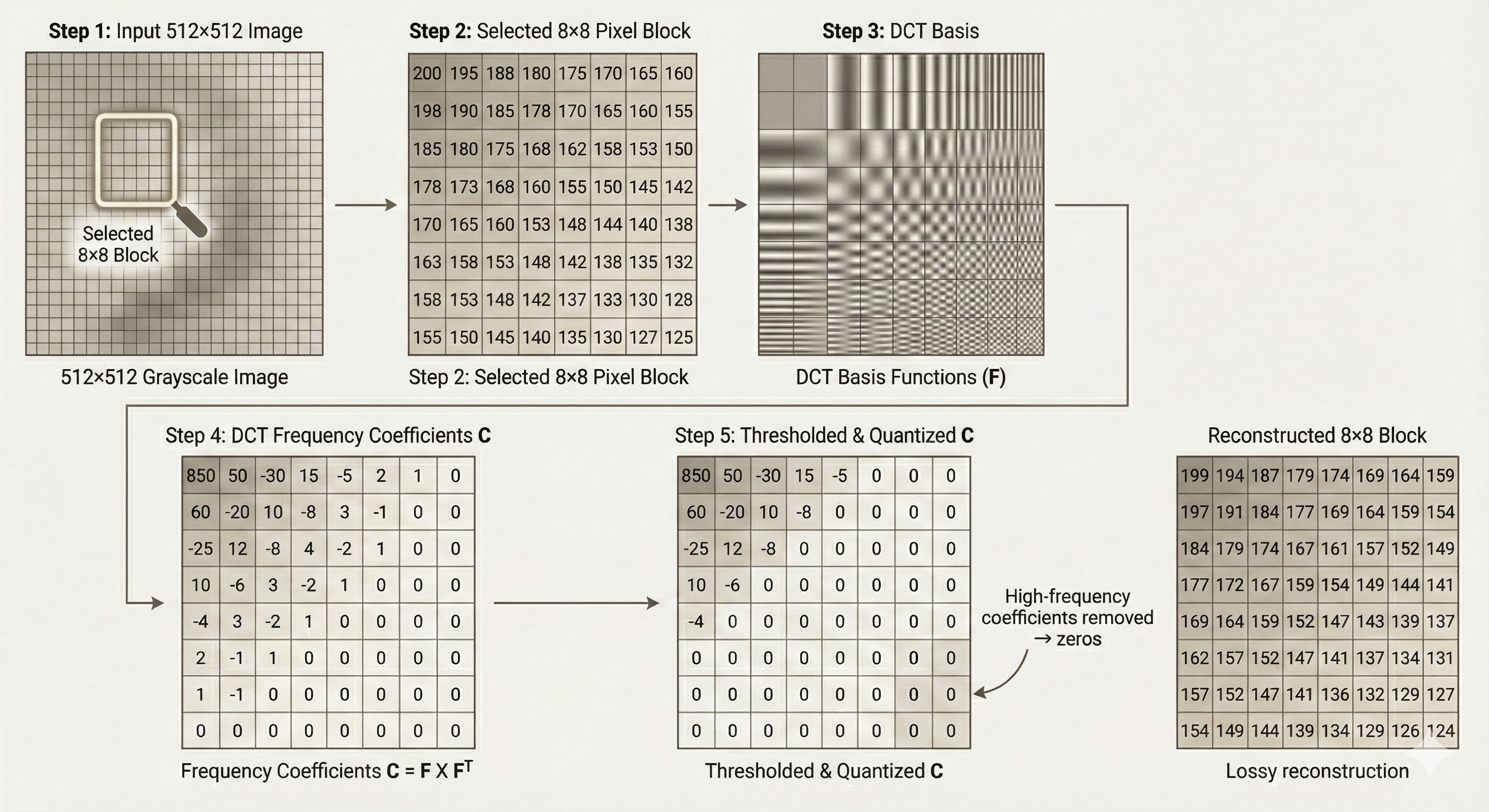

Break down the image into \(n\) blocks of size \(8 \times 8\) (64 pixels per block)

Build the Fourier matrix \(F_{64}\):

\[ F_{64} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 & \cdots & 1 \\ 1 & w & \cdots & w^{63} \\ 1 & w^2 & w^4 & w^{126} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \\ 1 & w^{63} & \cdots & w^{63 \times 63} \end{bmatrix} \]

where \(w = e^{2\pi i/64}\) is the 64th root of unity.

- Compute coefficients in the Fourier basis:

\[ c = Fx \]

where \(x\) is the 64-element pixel vector for one block.

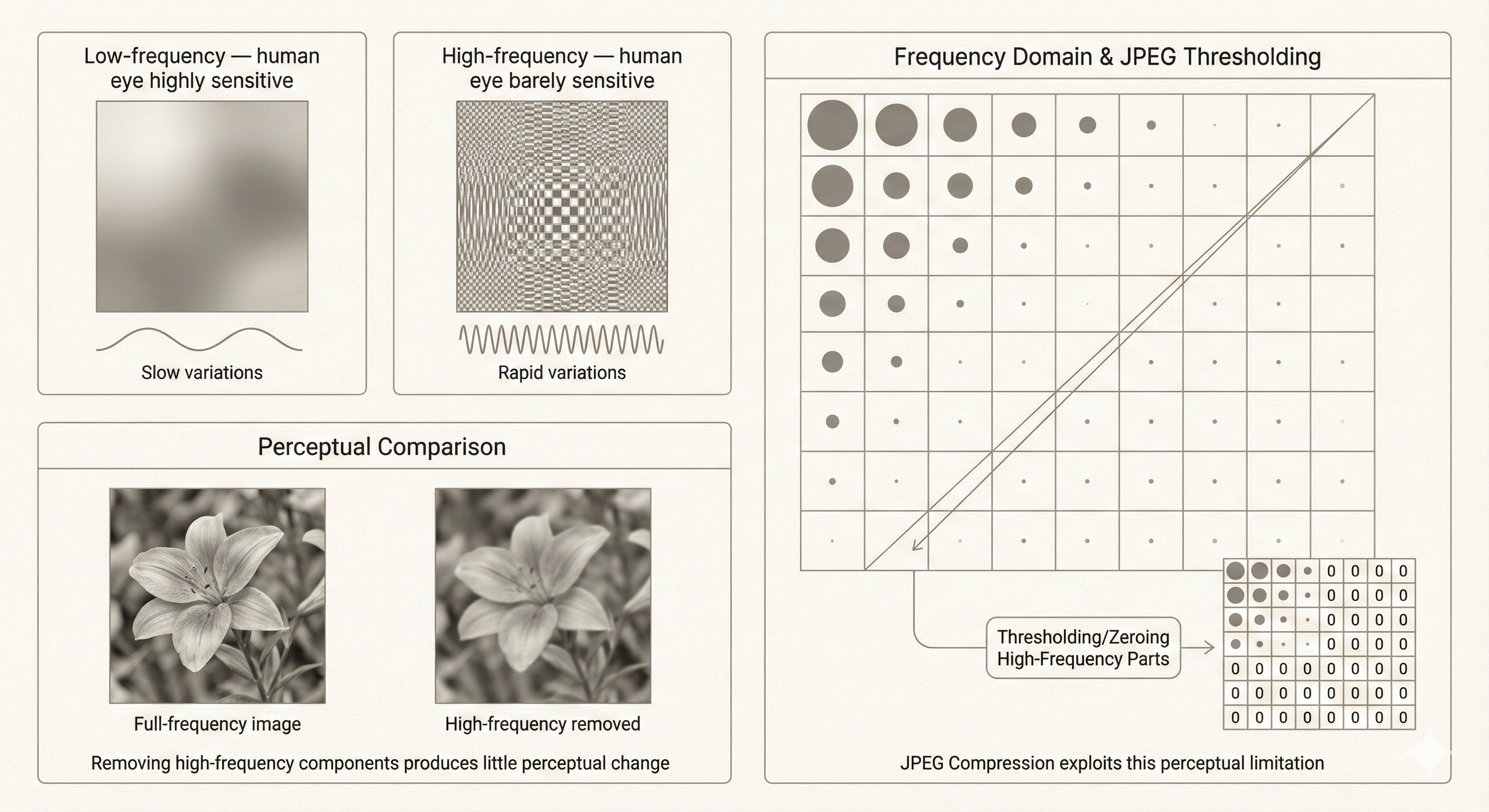

- Compression: Thresholding

Set small coefficients to zero:

\[ \hat{c} = \text{threshold}(c) \]

This produces a sparse matrix where most entries are zero.

Figure: JPEG compression pipeline - the image is transformed to the Fourier basis, small coefficients are discarded (thresholding), and the image is reconstructed from the remaining coefficients.

Figure: JPEG compression pipeline - the image is transformed to the Fourier basis, small coefficients are discarded (thresholding), and the image is reconstructed from the remaining coefficients.

- Reconstruction:

\[ \hat{x} = \sum_{i} \hat{c}_i v_i \]

where \(v_i\) are the Fourier basis vectors.

Key idea: Most energy in natural images concentrates in low-frequency components, so we can discard high-frequency coefficients with minimal perceptual loss.

3. Wavelets

Wavelets provide an alternative basis for image compression with some advantages over Fourier.

The Wavelet Basis

For \(n = 8\), the wavelet basis \(W\) consists of vectors:

\[ W = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}, \quad \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ -1 \\ -1 \\ -1 \\ -1 \end{bmatrix}, \quad \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ -1 \\ -1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}, \quad \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ -1 \\ -1 \end{bmatrix}, \quad \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ -1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}, \quad \ldots \]

Representation in Wavelet Basis

An 8-pixel vector from the standard basis can be represented as:

\[ p = c_1 w_1 + c_2 w_2 + \cdots + c_8 w_8 \]

In matrix form:

\[ p = W \begin{bmatrix} c_1 \\ c_2 \\ \vdots \\ c_8 \end{bmatrix} = Wc \]

Solving for Coefficients

\[ p = Wc \implies c = W^{-1}p \]

Advantage: Wavelets capture both spatial and frequency information, making them effective for images with edges and localized features.

4. Properties of a Good Basis

What makes a basis “good” for compression?

1. Fast Inverse

A good basis has a nice, fast inverse.

The matrix \(W^{-1}\) should be: - Easy to compute (ideally \(O(n \log n)\) or better) - Numerically stable

Examples: - Fourier basis: Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) computes \(F^{-1}\) in \(O(n \log n)\) - Wavelet basis: Fast Wavelet Transform also \(O(n \log n)\)

2. Few Is Enough

A few basis vectors are enough to reproduce the signal.

Most coefficients \(c_i\) should be small or zero, so we can: - Keep only the largest coefficients - Discard small coefficients with minimal error - Achieve high compression ratios

This is called sparsity in the transformed domain.

3. Orthogonal (No Redundant Information)

Basis vectors should be orthogonal.

Orthogonality ensures: - No redundancy between basis vectors - Each coefficient captures independent information - Simple formula: \(W^{-1} = W^T\) (up to normalization)

For compression, we want \(W^T W = I\) (orthonormal basis).

5. Change of Basis

General Formula

Let \(W\) be the matrix whose columns are the new basis vectors.

Let \(x\) be a vector in the old (standard) basis.

Let \(c\) be the coordinates in the new basis.

Relationship:

\[ x = Wc \]

To convert from old to new basis:

\[ c = W^{-1}x \]

If \(W\) is orthonormal, this simplifies to:

\[ c = W^T x \]

Example: For pixel vector \(p\) in standard basis and wavelet coefficients \(c\):

\[ p = Wc \quad \text{and} \quad c = W^{-1}p \]

6. Similar Matrices and Transformations

Setup

Say we have a linear transformation \(T\).

Then we can represent \(T\) with different matrices depending on the basis:

- With respect to basis \(v_1, v_2, \ldots, v_n\), we have matrix \(A\)

- With respect to basis \(w_1, w_2, \ldots, w_n\), we have matrix \(B\)

Relationship: \(A\) and \(B\) are similar matrices:

\[ A \sim B \quad \text{means} \quad B = M^{-1}AM \]

where \(M\) is the change of basis matrix.

Constructing Matrix \(A\)

After we know matrix \(A\), we know:

\[ T(v_1), T(v_2), \ldots, T(v_n) \]

Because for any vector:

\[ x = c_1 v_1 + c_2 v_2 + \cdots + c_n v_n \]

By linearity:

\[ T(x) = c_1 T(v_1) + c_2 T(v_2) + \cdots + c_n T(v_n) \]

If we know all the transformation results:

\[ \begin{align} T(v_1) &= a_{11}v_1 + a_{21}v_2 + \cdots + a_{n1}v_n \\ T(v_2) &= a_{12}v_1 + a_{22}v_2 + \cdots + a_{n2}v_n \\ &\vdots \\ T(v_n) &= a_{1n}v_1 + a_{2n}v_2 + \cdots + a_{nn}v_n \end{align} \]

We can form the matrix:

\[ A = \begin{bmatrix} | & | & & | \\ a_1 & a_2 & \cdots & a_n \\ | & | & & | \end{bmatrix} \]

where \(a_i\) is the coefficient vector for \(T(v_i)\).

Special Case: Eigenvector Basis

If all \(v_i\) happen to be eigenvectors:

\[ T(v_i) = \lambda_i v_i \]

Then \(A\) is a diagonal matrix of eigenvalues:

\[ A = \begin{bmatrix} \lambda_1 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ 0 & \lambda_2 & \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \cdots & \lambda_n \end{bmatrix} \]

Application to compression: If we can find eigenvectors of the image covariance matrix, we can use PCA (Principal Component Analysis) for compression. This seems to be the perfect way of compression, but given the computational cost, in practice we don’t use this approach for large images.

Summary

| Concept | Key Idea |

|---|---|

| Image as Vector | \(512 \times 512\) image = vector in \(\mathbb{R}^{262,144}\) |

| JPEG Compression | Change to Fourier basis, threshold small coefficients |

| Wavelet Basis | Alternative basis capturing spatial + frequency information |

| Good Basis Properties | Fast inverse, sparsity (few coefficients enough), orthogonal |

| Change of Basis | \(x = Wc\) where \(W\) has new basis vectors as columns |

| Similar Matrices | \(B = M^{-1}AM\) represents same transformation in different basis |

| Eigenvector Basis | Gives diagonal matrix (ideal but computationally expensive) |

Key insight: The effectiveness of compression depends on choosing a basis where the signal is sparse (most coefficients are small). Different bases work best for different types of data—Fourier for smooth images, wavelets for images with edges, eigenvectors (PCA) for data-specific optimal compression.