Gilbert Strang’s Calculus: The Exponential Function

Properties

- \(\frac{d}{dx}e^x = e^x\)

- \(e^a\cdot e^b = e^{a+b}\)

- If \(y=e^{cx}\), then \(\frac{dy}{dx}=cy=c e^{cx}\)

Infer the value of \(e\)

Start from the condition that defines the exponential function:

- \(y(0)=1\)

- \(\frac{dy}{dx}=y\)

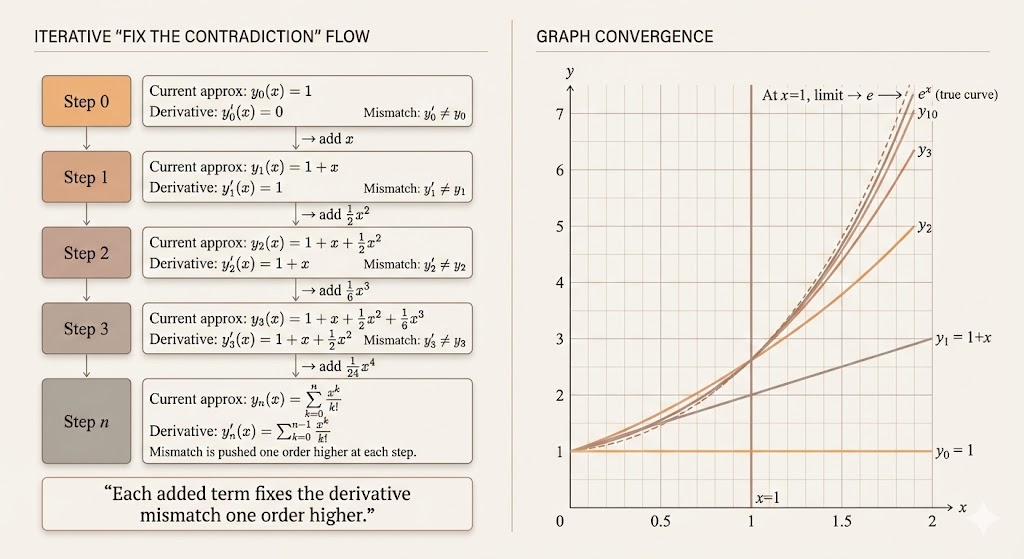

If we start with \(y(x)=1\), then

- \(y(x)=1\)

- \(y'(x)=0\)

This cannot satisfy \(y'=y\), so we need to add an \(x\) term.

Step 1:

- \(y(x)=1+x\)

- \(y'(x)=1\)

Now \(y'\) is still missing the \(x\) term, so we add a quadratic term.

Step 2:

- \(y(x)=1+x+\frac{1}{2}x^2\)

- \(y'(x)=1+x\)

Now \(y'\) is missing \(\frac12 x^2\), so we add a cubic term.

Step 3:

- \(y(x)=1+x+\frac{1}{2}x^2+\frac{1}{6}x^3\)

- \(y'(x)=1+x+\frac{1}{2}x^2\)

Key observation:

- This is an infinite correction loop.

- Each time we add a term \(\frac{1}{n!}x^n\), its derivative becomes \(\frac{1}{(n-1)!}x^{n-1}\), exactly matching the previous missing term.

So eventually, \[ y(x)=1+x+\frac{1}{2}x^2+\frac{1}{6}x^3+\cdots+\frac{1}{n!}x^n+\cdots \]

When \(x=1\), we get \[ e=1+1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{6}+\frac{1}{24}+\cdots+\frac{1}{n!}+\cdots \approx 2.718281828459045. \]

We are not guessing \(e^x\). We are forcing a function to equal its own derivative, and factorial coefficients are exactly what make this possible.

Graph of \(e^x\)

- At \(x=0\), \(y=1\).

- At \(x=1\), \(y=e\).

- For \(x<0\), \(0<e^x<1\).

- \(e^{-x}=\frac{1}{e^x}\).

- The slope is always positive and increases with \(x\).

Example: Computing Compound Interest

Suppose you have $$1 in the bank, with 100% annual interest.

If interest is compounded yearly:

- End of year 1: \(\$2\)

- End of year 2: \(\$4\)

- End of year 3: \(\$8\)

So after \(n\) years, the amount is \(2^n\).

If the same annual rate is compounded monthly, then after one year: \[ \left(1+\frac{1}{12}\right)^{12} \approx 2.613035290224676. \]

If it is compounded daily: \[ \left(1+\frac{1}{365}\right)^{365} \approx 2.7145674820219727. \]

As compounding becomes more frequent, the value approaches \(e\): \[ \left(1+\frac{1}{N}\right)^N \to e. \]

That is why \(e\) naturally appears in continuous growth.