Lecture 4: Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors

Eigenvectors

\[ Ax=\lambda x \]

An eigenvector \(x\) is a nonzero vector whose direction remains unchanged by a linear transformation, up to a scaling factor \(\lambda\).

A \(n \times n\) full rank matrix has \(n\) eigenvectors.

Powers and Inverse

\[ A^2x=A(\lambda x)=\lambda(Ax)=\lambda^2x \]

\[ A^kx=\lambda^kx \]

\[ A^{-1}x=\frac{1}{\lambda}x \]

\[ e^{At}x=e^{\lambda t}x \]

Proof:

\[ e^{At}x=(I+At+\frac{A^2t^2}{2!}+\dots)x= x+\lambda tx+\frac{\lambda^2 t^2}{2!}x+\dots=e^{\lambda t}x \]

Special Cases

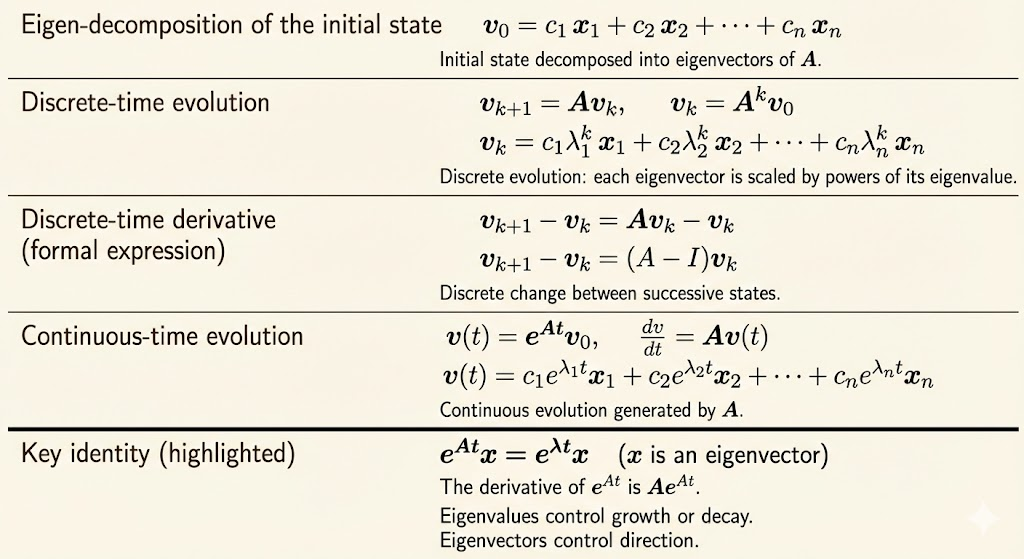

Compute \(v_k = A^k v\). Initial status is \(v_0.\)

First, decompose \(v_0\) to the linear combination of eigenvectors:

\[ v_0=c_1x_1+\dots+c_nx_n \]

\[ v_k=A^kv_0=c_1\lambda_1^kx_1+\dots+c_n\lambda_n^kx_n \]

One of the most important use cases of eigenvectors is to solve the difference equation:

\[ v_{k+1}=Av_k \]

And the solution to discrete steps is:

\[ v_k=c_1\lambda_1^kx_1+\dots+c_n\lambda_n^kx_n \]

The solution to the continuous differential equation:

\[ \frac{\partial v}{\partial t}=Av \]

is:

\[ v(t)=c_1e^{\lambda_1 t}x_1+\dots+c_ne^{\lambda_n t}x_n \]

Similar Matrices

A matrix \(B\) is similar to another matrix \(A\) if \(B=M^{-1}AM\).

Similar matrices have the same eigenvalues.

Proof:

Suppose \(B\) is similar to \(A\), and \(y\) is an eigenvector of \(B\), \(\lambda\) is the eigenvalue.

\[ By=M^{-1}AMy=\lambda y \]

\[ MM^{-1}AMy=AMy=\lambda My \]

\[ A(My)=\lambda(My) \]

We can see the eigenvector of \(A\) is \(My\), and the eigenvalue remains \(\lambda\).

BA and AB Have Same Eigenvalues

We can prove \(BA\) and \(AB\) have the same eigenvalues by proving they are similar:

\[ M^{-1}(AB)M=BA \]

Proof:

Set \(M\) as \(B^{-1}\), we can prove \(AB\) and \(BA\) are similar:

\[ BABB^{-1}=BA \]

Note: \(B\) should be invertible.

Non-linearity

In general, we cannot say:

- \(\mathrm{Eig}(AB)=\mathrm{Eig}(A)\mathrm{Eig}(B)\)

- \(\mathrm{Eig}(A+B)=\mathrm{Eig}(A)+\mathrm{Eig}(B)\)

because \(A\) and \(B\) may not share the same eigenvectors.

Key Facts of Symmetric Matrices

- The eigenvalues of real symmetric matrices are always real numbers.

- The eigenvectors of symmetric matrices are orthogonal.

Example:

\[ S=\begin{bmatrix}0&1\\1&0\end{bmatrix} \]

The eigenvalues are \(\lambda=1,-1\), the eigenvectors are:

\[ x_1=\begin{bmatrix}1\\1\end{bmatrix},\quad x_2=\begin{bmatrix}1\\-1\end{bmatrix} \]

Now we want to show the relation between \(S\) and \(\Lambda\).

We claim that \(S\) is similar to \(\Lambda\), because \(S\) and \(\Lambda\) have the same eigenvalues:

\[ S \sim \begin{bmatrix}1&0\\0&-1\end{bmatrix} \]

\[ M^{-1}SM=\Lambda \]

If we set \(M\) as the eigenvectors matrix, we get:

\[ MM^{-1}SM=SM=M\Lambda \]

Check:

\[ S\begin{bmatrix}x_1&x_2\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}Sx_1&Sx_2\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}x_1&-x_2\end{bmatrix} \]

\[ \begin{bmatrix}x_1&x_2\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}1&0\\0&-1\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}x_1&-x_2\end{bmatrix} \]

General Case

If matrix \(A\) has eigenvectors \(X\) and eigenvalues \(\Lambda\), then:

\[ AX=X\Lambda \]

and

\[ A=X\Lambda X^{-1} \]

\[ A^2=X\Lambda X^{-1}X\Lambda X^{-1}=X\Lambda^2 X^{-1} \]

When the matrix is symmetric, the eigenvectors are orthogonal:

\[ S=Q\Lambda Q^{-1}=Q\Lambda Q^\top \]

Anti-symmetric Matrix

Example:

\[ A=\begin{bmatrix}0&1\\-1&0\end{bmatrix} \]

This matrix rotates all \(x\) by 90 degrees, so there is no \(x\) that can preserve its direction.

Find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of \(A\):

\[ Ax=\lambda x \]

\[ (A-\lambda I)x=0 \]

\[ \det(A-\lambda I)=0 \]

By looking at the matrix \(A-\lambda I\):

\[ \det(A-\lambda I)=\det \begin{bmatrix}-\lambda&1\\-1&-\lambda \end{bmatrix} \]

\[ \lambda^2+1=0 \]

\[ \lambda^2=-1,\quad \lambda=i,-i \]

Exercise

1. Compute the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of \(A\) and \(A^{-1}\).

\[ A=\begin{bmatrix}0&2\\1&1\end{bmatrix},\quad A^{-1}=\begin{bmatrix}-\frac{1}{2}&1\\\frac{1}{2}&0\end{bmatrix} \]

Solution:

- Eigenvalues of \(A\) are \(2\) and \(-1\)

- Eigenvalues of \(A^{-1}\) are \(\frac{1}{2}\) and \(-1\)

- Eigenvectors of \(A\) and \(A^{-1}\) are both:

\[ x_1=[1,1],\quad x_2=[-2,1] \]

\(A\) and \(A^{-1}\) have the same eigenvectors, and eigenvalues of \(A^{-1}=\frac{1}{\lambda}\), where \(\lambda\)s are eigenvalues of \(A\).

2. The eigenvalues of \(A\) equal the eigenvalues of \(A^\top\). This is because \(\det(A-\lambda I)\) equals \(\det(A^\top-\lambda I)\). This is true because the determinant of a matrix equals the determinant of its transpose.

Show an example where the eigenvectors of \(A\) and \(A^\top\) are not the same.

Example:

\[ \begin{bmatrix}1&2\\3&4\end{bmatrix} \]

3. (a) Factor these two matrices into \(A=X\Lambda X^{-1}\):

\[ A=\begin{bmatrix}1&2\\0&3\end{bmatrix},\quad A=\begin{bmatrix}1&3\\1&3\end{bmatrix} \]

Solution:

\[ \begin{bmatrix}1&2\\0&3\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}1&1\\0&1\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}1&0\\0&3\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}1&-1\\0&1\end{bmatrix} \]

\[ \begin{bmatrix}1&3\\1&3\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}-3&1\\1&1\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}0&0\\0&4\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}-\frac{1}{4}&\frac{1}{4}\\\frac{1}{4}&\frac{3}{4}\end{bmatrix} \]

- If \(A=X\Lambda X^{-1}\), then \(A^3=()()()\) and \(A^{-1}=()()()\)?

Solution:

\[ A^3=X\Lambda^3X^{-1} \]

\[ A^{-1}=X\Lambda^{-1}X^{-1} \]