Goodfellow Deep Learning — Chapter 12.5: Other Applications

Recommendation Systems

Early recommendation systems relied on very limited input information, typically user IDs and item IDs, with generalization achieved solely through patterns of interaction between users and items.

Under this limitation, the only generalization method is to rely on the pattern similarity between different users and items. For example, assume user A and B both like items 1, 2, 3, then if A likes item 4, then item 4 can be recommended to user B.

The algorithm based on this principle is called Collaborative Filtering.

Matrix Factorization

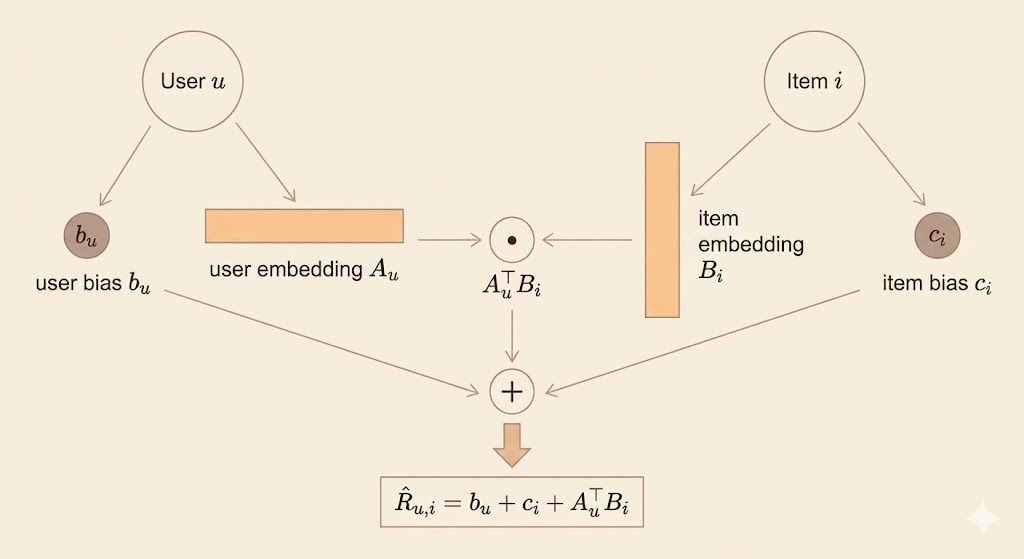

In matrix factorization–based recommender systems, each user and each item is represented by a low-dimensional latent vector:

- \(A_u \in \mathbb{R}^k\): the latent representation (embedding) of user \(u\), capturing the user’s preferences across \(k\) latent factors

- \(B_i \in \mathbb{R}^k\): the latent representation (embedding) of item \(i\), capturing the item’s attributes or characteristics in the same latent space

These latent factors model personalized interactions between users and items.

Bias Terms

To account for systematic effects that are independent of user–item interactions, the model includes bias terms:

- \(b_u\): the user bias, representing the overall tendency of user \(u\) to give higher or lower ratings

- \(c_i\): the item bias, representing the overall popularity or quality of item \(i\)

Including these bias terms allows the latent factors to focus on modeling individualized preferences rather than global effects.

Prediction Model

The predicted rating (or preference score) of user \(u\) for item \(i\) is given by:

\[ \hat{R}_{u,i} = b_u + c_i + A_u^\top B_i \]

where the dot product \(A_u^\top B_i\) captures the interaction between the user and item latent factors.

Interpretation

This formulation decomposes a user’s rating into three components:

- User-specific tendency (\(b_u\))

- Item-specific popularity (\(c_i\))

- Personalized interaction between the user and item (\(A_u^\top B_i\))

Together, these components provide a compact, interpretable, and effective model for collaborative filtering, and form the foundation of many successful recommender systems, including those developed during the Netflix Prize competition.

Cold-Start Problem

A fundamental limitation of collaborative filtering is the cold-start problem: when new users or items have no interaction history, their preferences cannot be inferred from user–item patterns alone.

A common solution is to incorporate side information, such as user attributes or item content, enabling the model to make predictions even in the absence of interaction data and leading to content-based or hybrid recommender systems.

Exploration and Exploitation

Recommendation problems go beyond standard supervised learning because feedback is only observed for items that the system chooses to recommend, resulting in biased and incomplete data.

In many cases, the system cannot observe user responses to non-recommended items, and may even lack information about users who were never exposed to any recommendation.

This setting is naturally modeled as a contextual bandit problem. The central challenge is the exploration–exploitation tradeoff:

- Exploitation: Recommend items that are currently known to perform well

- Exploration: Try new items to gather information about user preferences

Knowledge as Entities and Relations

Knowledge is represented using symbolic facts, typically in the form of triples:

- (subject, relation, object) e.g., (Paris, capital_of, France)

or more abstractly:

- (entity_i, relation_j, entity_k)

Relations can be: - Binary (most common) - Directional - Non-numeric (not just mathematical relations like <)

This structure is the foundation of knowledge graphs (e.g., Freebase, WordNet, Wikidata).

Distributed Representations for Entities and Relations

Instead of treating entities and relations as discrete symbols, deep learning maps them into continuous vector spaces:

- Entities → embedding vectors

- Relations → embedding vectors or operators

Key idea: > Learning embeddings allows the model to generalize beyond observed facts.

Early approaches: - Linear relation embeddings - Treat relations as transformations acting on entity embeddings

This connects language modeling with knowledge modeling, since both rely on distributed representations.

Link Prediction as a Core Task

A central application is link prediction:

Predict whether a missing fact in a knowledge graph is likely to be true.

Example: - Given (Paris, capital_of, ?) - Predict France

This is framed as: - Scoring candidate triples - Ranking true facts above corrupted (false) ones

Negative samples are usually created by corrupting known true facts (e.g., replacing one entity).

Evaluation Challenges

Evaluation is difficult because:

- Datasets usually contain only known true facts

- An unseen fact may be either false or simply missing

Common evaluation strategy: - Rank the true fact among corrupted alternatives - Measure metrics like top-k accuracy

This reflects a broader challenge: open-world knowledge.

Attributes and Richer Relations

Beyond relations, entities may have attributes:

- (entity, attribute) e.g., (Paris, population)

This enriches the representation and connects structured knowledge with real-valued information.

From Knowledge Representation to Reasoning and QA

The long-term goal is to combine:

- Knowledge representation (facts, entities, relations)

- Reasoning (inferring new facts)

- Natural language understanding (questions expressed in text)

This enables: - Question answering systems - Reasoning over multiple facts - Integration of language models with knowledge bases