Gilbert Strang’s Calculus: Derivative of sin x and cos x

Goal

We want to prove:

- \(\frac{d}{dx}(\sin x)=\cos x\)

- \(\frac{d}{dx}(\cos x)=-\sin x\)

These formulas are true when angles are measured in radians.

Three facts we use

Pythagorean identity: \[ \sin^2\theta+\cos^2\theta=1. \]

Angle addition for sine: \[ \sin(x+h)=\sin x\cos h+\cos x\sin h. \]

Angle addition for cosine: \[ \cos(x+h)=\cos x\cos h-\sin x\sin h. \]

Circular motion picture

On the unit circle, the point at angle \(t\) is \[ (\cos t,\sin t). \] So proving derivatives of \(\sin t\) and \(\cos t\) is equivalent to understanding velocity components in circular motion.

Why radians matter

\[ 2\pi\ \text{radians}=360^\circ. \]

Only in radian measure do we get the clean limit \[ \lim_{h\to 0}\frac{\sin h}{h}=1, \] which drives both derivative proofs.

Geometric inequalities

Two properties we need are:

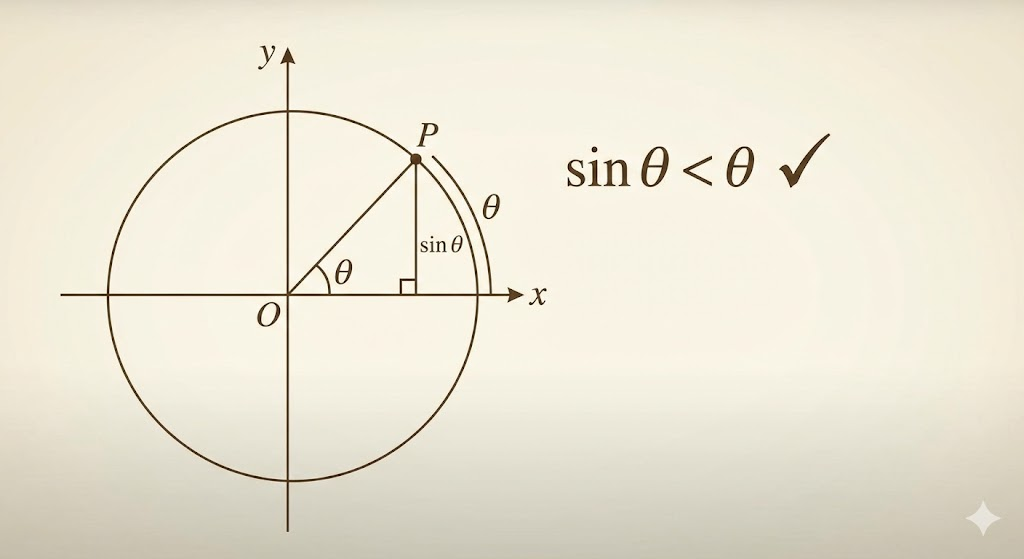

- \(\sin\theta<\theta\) for \(\theta>0\)

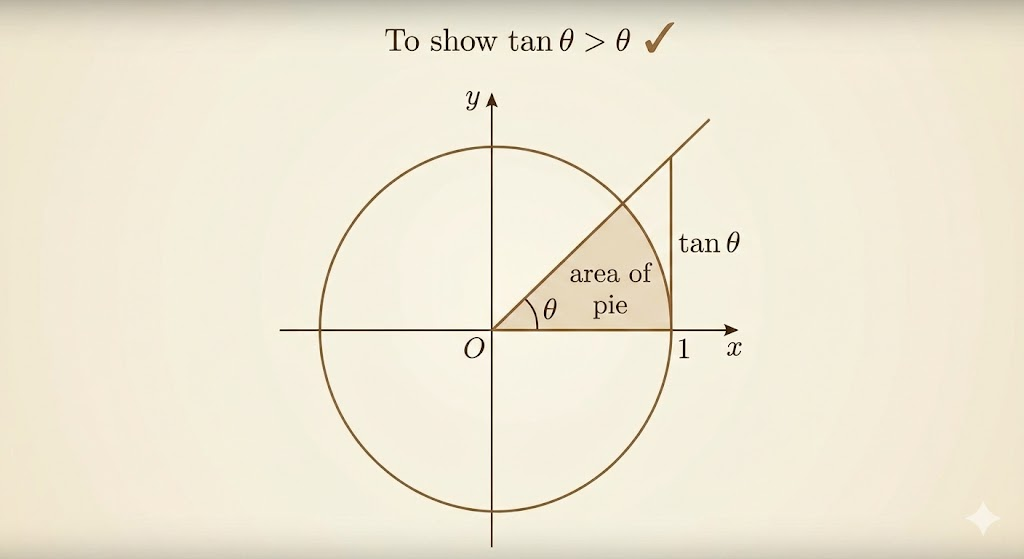

- \(\tan\theta>\theta\) for \(0<\theta<\frac\pi2\)

For \(\sin\theta<\theta\): in the unit circle, the chord subtended by angle \(\theta\) is shorter than the arc, and that arc length is exactly \(\theta\) (in radians). The vertical leg of the inscribed right triangle has length \(\sin\theta\), and this leg is shorter than the chord. Therefore \[ \sin\theta < \text{chord} < \theta. \] So \(\sin\theta<\theta\).

For \(\tan\theta>\theta\): compare areas. The sector area is \[ A_{\text{sector}}=\frac12\theta \] on the unit circle, while the outer right triangle formed by the radius and tangent line has area \[ A_{\triangle}=\frac12\tan\theta. \] Because the sector lies strictly inside that tangent triangle, \[ \frac12\theta<\frac12\tan\theta \;\Rightarrow\;\theta<\tan\theta. \]

From \(\theta<\tan\theta=\frac{\sin\theta}{\cos\theta}\), we get \[ \cos\theta<\frac{\sin\theta}{\theta}<1. \] By squeeze theorem, \[ \lim_{\theta\to 0}\frac{\sin\theta}{\theta}=1. \]

The missing limit: (cos h - 1)/h -> 0

Yes, this part should be proved explicitly.

Use \[ \cos h-1=-2\sin^2\left(\frac h2\right). \] Then \[ \frac{\cos h-1}{h} =-\sin\left(\frac h2\right)\cdot \frac{\sin(h/2)}{h/2}. \] As \(h\to 0\), \[ \sin\left(\frac h2\right)\to 0, \qquad \frac{\sin(h/2)}{h/2}\to 1, \] so \[ \lim_{h\to 0}\frac{\cos h-1}{h}=0. \]

Prove d(sin x)/dx = cos x

Using angle addition: \[ \frac{\sin(x+h)-\sin x}{h} =\frac{\sin x(\cos h-1)+\cos x\sin h}{h} =\sin x\frac{\cos h-1}{h}+\cos x\frac{\sin h}{h}. \] Take \(h\to 0\): \[ \frac{d}{dx}(\sin x) =\sin x\cdot 0+\cos x\cdot 1 =\cos x. \]

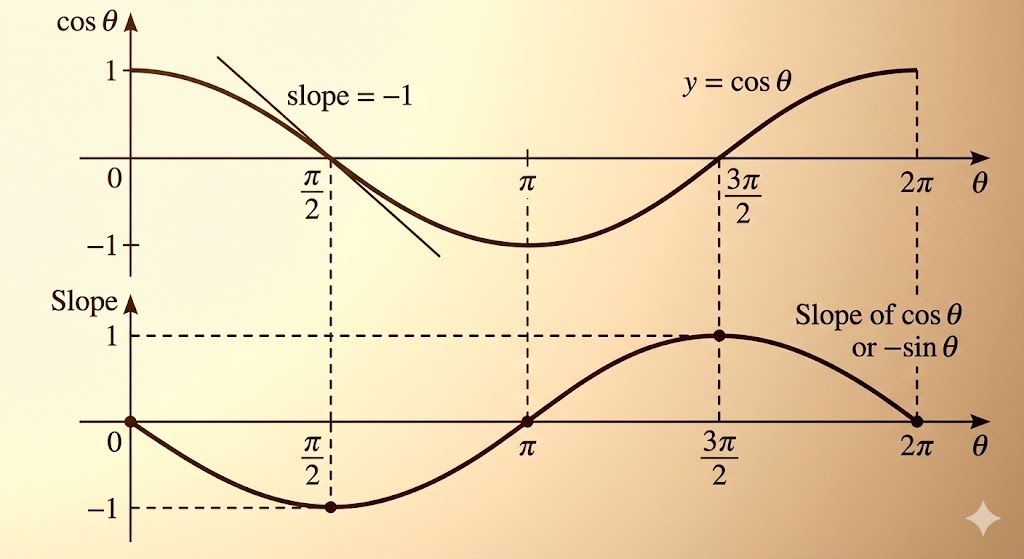

Prove d(cos x)/dx = -sin x

Again from angle addition: \[ \frac{\cos(x+h)-\cos x}{h} =\frac{\cos x(\cos h-1)-\sin x\sin h}{h} =\cos x\frac{\cos h-1}{h}-\sin x\frac{\sin h}{h}. \] Take \(h\to 0\): \[ \frac{d}{dx}(\cos x) =\cos x\cdot 0-\sin x\cdot 1 =-\sin x. \]

Takeaway. The two derivative formulas rest on two core limits, \(\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{\sin h}{h}=1\) and \(\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{\cos h-1}{h}=0\), which come from unit-circle geometry and radian measure.